How Do I Draw A Scientific Model

Scientists do not but utilise words but also diagrams, graphs and images to convey their knowledge. In other words, they communicate through a complex combination of semiotic (meaning-making) systems to generate multimodal texts (Polias, 2016).

Students need to be able to both empathise these visual representations and to create their own. The creation of these representations provides a way for students to play with their emerging ideas, build and extend existing knowledge while also learning advisable visual conventions (Ainsworth, Prain & Tytler, 2011).

The procedure of drawing diagrams as well as explaining and justifying them assists students to develop science understanding (Waldrip, Prain & Carolan, 2010). The generation of visual representations should thus be idea of as a thinking tool that both develops and shows pupil understanding. Enquiry has shown that the utilise of workbooks that are lined on one side and bare on the other non only encourage students to use drawing to explore and present ideas, simply also improve student engagement with learning (Tytler, Prain & Hubber, 2018).

4 strategies to support students to draw visual representations of their scientific knowledge are:

- critiquing and creating diagrams

- joint construction of diagrams

- writing and drawing chemic reactions

- transforming data

There is besides a note about the use of concept maps.

Critiquing and creating diagrams

Inside Science, students are presented with a range of diagrams and models that represent abstruse and circuitous processes. Teaching students the skills to critique visual and concrete representations in Science empowers them to place positive and productive aspects that they tin can and so incorporate into their own diagrammatic representations.

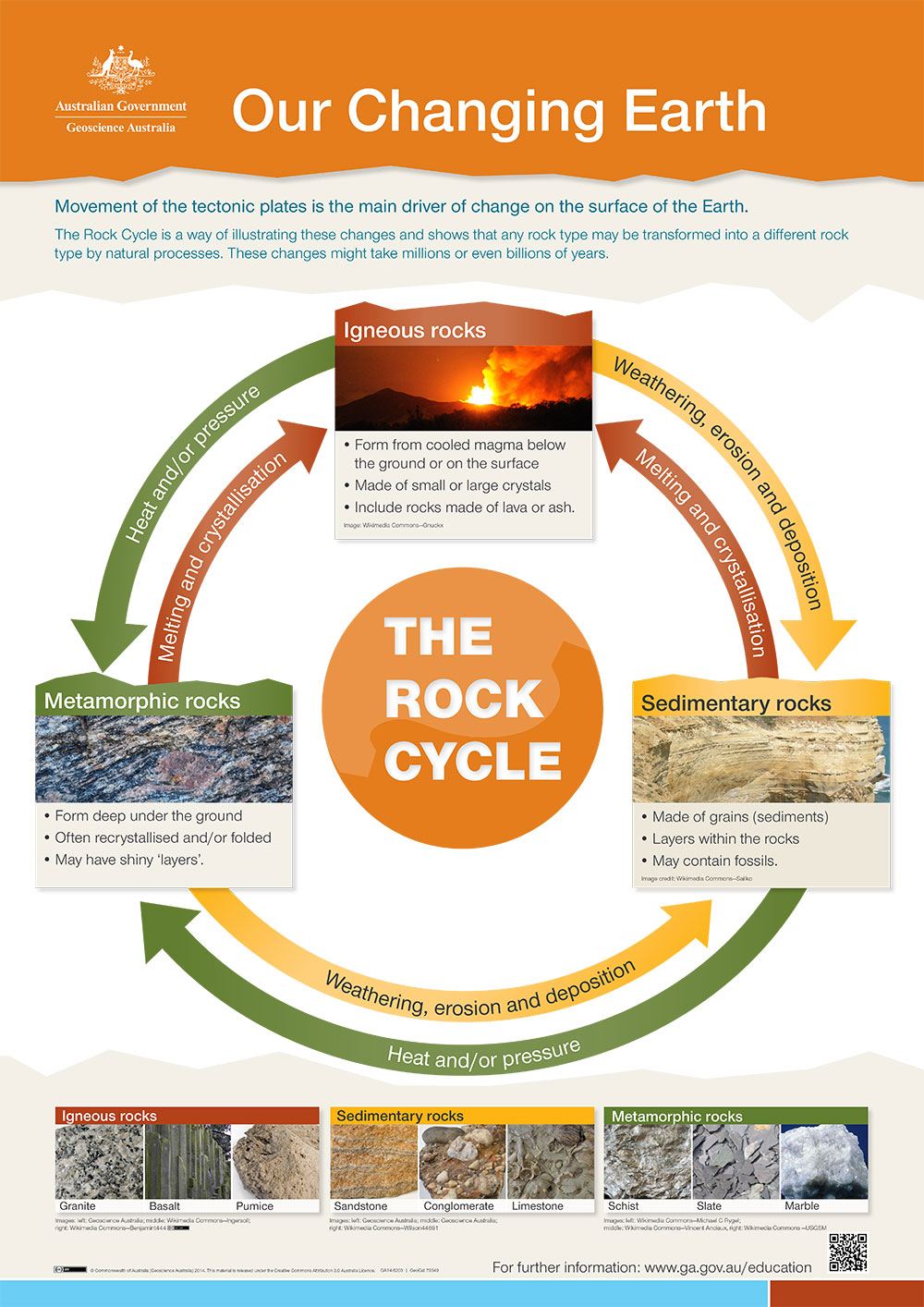

The following activeness has been adapted from Tytler, Prain and Hubber (2018), and focuses on the rock cycle that is taught in Year 7 or 8 (VCSSU102). One visual representation of the stone cycle that can exist used is also below.

This strategy can exist adapted to back up learning related to any of the Science Understanding content descriptions.

- Present students with five–seven visual representations of the rock cycle.

- In groups of iii or 4, students critique the dissimilar diagrammatic forms. For example, they could:

- note features that they discover helpful or confusing

- write down what is shown well and what is not shown well.

- The teacher supports the students' critique by asking question to arm-twist more specific responses (for example, "What do you lot mean by 'everything'?"; "What do you like about how the sedimentation process is drawn?")

- Students construct their own representation of the rock cycle.

Source: Our changing world: The rock cycle, Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia), 2014.

Joint structure of diagrams

Joint construction is a collaborative learning action that provides opportunities for the teacher and students to share their knowledge and learn from one another (HITS Strategy 5). Articulation construction tin can be used to back up students to develop their literate skills to depict visual representations of knowledge.

- Provide students with a written definition of a process.

- Have students discuss the definition in pairs.

- Inquire students to draw a diagram to stand for the process.

- Students explain their diagram to the class.

- Students receive feedback from their peers and teacher about their diagram.

- Students are given the opportunity to act on the feedback to refine their diagram.

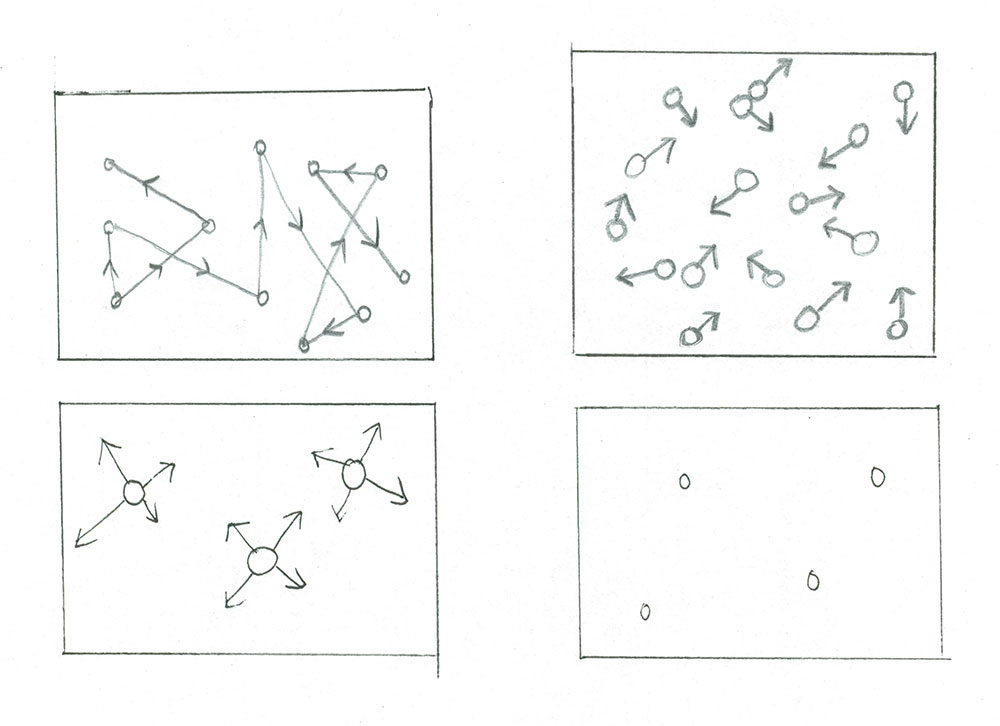

The images below are drawings made by Year 7 students to show the relationship betwixt Brownian movement and changes of state (VCSSU096, VCSIS110).

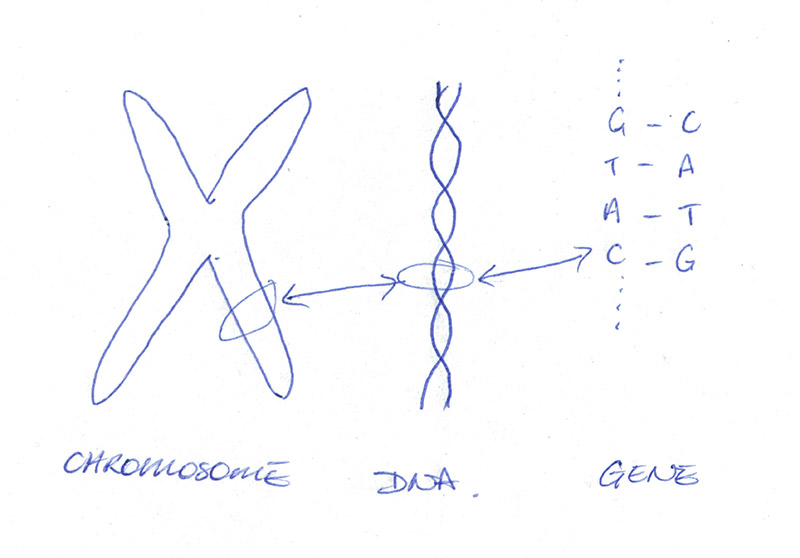

The image below is a cartoon fabricated by a Year 10 student to show the human relationship between chromosomes, Dna and genes (VCSSU119, VCSIS137).

Writing and cartoon chemical reactions

A chemical formula is a remarkably brusk and reduced mode of representation (Taasoobshirazi & Glynn, 2009). While chemical formulas enable efficient communication between scientists, they ready comprehension barriers for students (Taasoobshirazi & Glynn, 2009).

Helping students to move between modes of representation of chemical formulas should help them to develop both their comprehension of the meaning-making system of chemical science, but too of the chemical science involved in the represented chemical reactions.

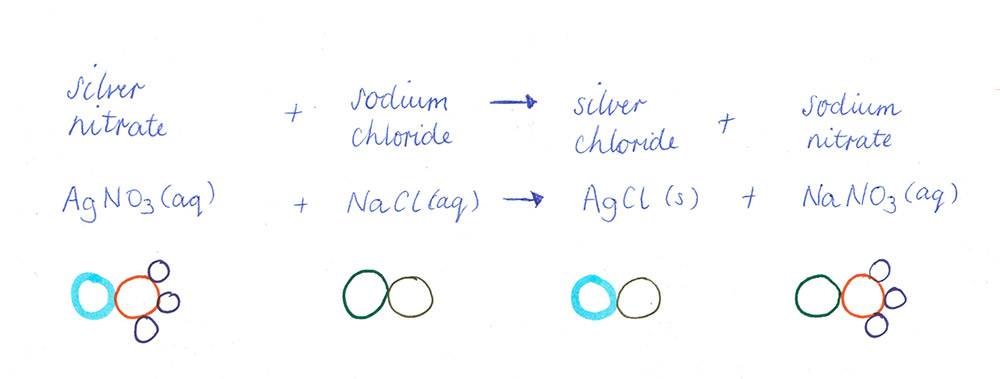

The example beneath can be used in a Year 9 or ten class (VCSSU124, VCSIS137). The post-obit educatee sample is from a Yr 9 class.

- The instructor or educatee writes the chemical reaction in words.

- With assistance, the students write down the chemic formula for the reactants and products.

- The students draw molecular diagrams of the reactants and products.

- The students balance the chemical equation past cartoon additional molecular diagrams for the reactants and products.

- Once the drawings are counterbalanced, the students count the molecules on each side of the reaction and balance the chemical reaction.

- Students can rewrite the chemic reaction in words, adding in the number of molecules of each reactant and product.

In the first part of this video, Emily Rochette demonstrates how teachers can assist students to motion betwixt various representations of chemic reactions. After observing several chemical reactions, students are supported to transcribe written chemical reactions into chemical equations and molecular diagrams.

Literacy in Practice Video: Science - Diagrams

In the second role of the video, Emily discusses the importance of drawing diagrams in Science. She emphasises the features of scientific drawings (equally opposed to everyday drawings) to better develop her students' drawing skills.

Student prompts

- What accept your teachers done to support your drawing skills in Scientific discipline?

- What do you lot sympathize to be the difference between everyday drawings and scientific drawings?

- How might cartoon chemical reactions help you to sympathize how chemicals react?

Read the in-depth notes for this video.

Transforming data

In Science, data and concepts are represented in multiple modes (forms of communication). Every bit well as using written language, scientists use images, graphs, diagrams, and models, to proper name a few.

Different modes of communication present information in different ways, and not any one mode tin requite you lot a consummate meaning. In other words, each mode of advice has benefits and constraints.

Transforming, or transducing, content into different forms can exist challenging for students because some significant might exist gained or lost when moving between modes (Jakobson et al., 2018). Students require support to transform data because irresolute the way in which information is presented requires both the form (structure) and content to be altered (Jakobson et al., 2018).

Assisting students to transform data from 1 form to another:

- improves their literacy skills in Science

- helps them to understand the benefits and limitations of different forms of representation (or modal affordance)

- helps them to develop and write explanations for their observations.

Literacy in Science Video: Explained

In this video, Dr Emily Rochette discusses some of the literacy challenges associated with learning in Science. These include representing scientific concepts or phenomena, whether orally, in writing or through diagrams, and writing a range of text types, particularly in relation to applied activities. Dr Rochette suggests it is important for teachers to model how to incorporate scientific representations into written responses.

Instructor prompts

- How do you support your students to make meaningful links betwixt the microscopic, macroscopic and symbolic levels of representation in chemical science?

- How do you lot model writing each department of a practical report in chemistry?

Audio transcript

[gentle music]

[Dr Emily Rochette ] Then one of the challenges in chemistry is helping students to make the connections between the macroscopic, the microscopic, and the symbolic levels of representations.

For case, when nosotros teach balancing chemical reactions in inferior chemical science, students right away are presented with a symbolic representation of these substances, and they need to be able to account for how these substances are changing in chemical reactions.

So what nosotros exercise is we try to represent these chemical formulae in terms of particle models of the atom.

We use tables in order to account for what's happening to the individual atoms and how they're being rearranged in order to help students be able to articulate what's happening at the microscopic level.

And this becomes quite challenging because not only exercise students have to practise this orally, they as well accept to do this through writing, and whether that means representing different substances through pictures, just also using the scientific terminology in longer written responses.

Things like this go quite complicated when they're incorporated into applied work, for example, considering there are many dissimilar text types that are presented in practical piece of work.

For case, creating a procedure or a method with a pace-wise way of doing things and interpreting the science, things like this.

But as well one item area that'due south quite difficult for students in applied work is the discussion where they need to display their understanding of these three dissimilar representations.

So practising that a lot during course fourth dimension through word, through written responses, and in particular using students' responses that might be unsophisticated from a scientific level, showing them in class and modelling the correct use of this terminology becomes very, very important.

[gentle music]

The following activeness, and student sample, comes from a Year x class (VCSSU133, VCSIS137, VCSIS138), and has been adapted from Jacobson et al. (2018). While the end-production of this strategy is for students to write an explanation for their observations, the strategy can be adapted to focus on developing students' ability to stand for scientific information in any mode.

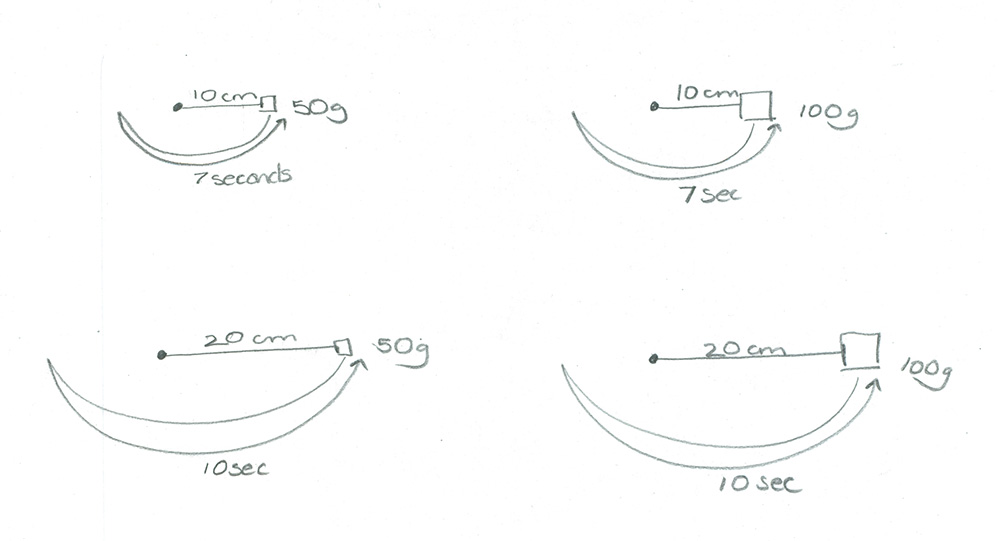

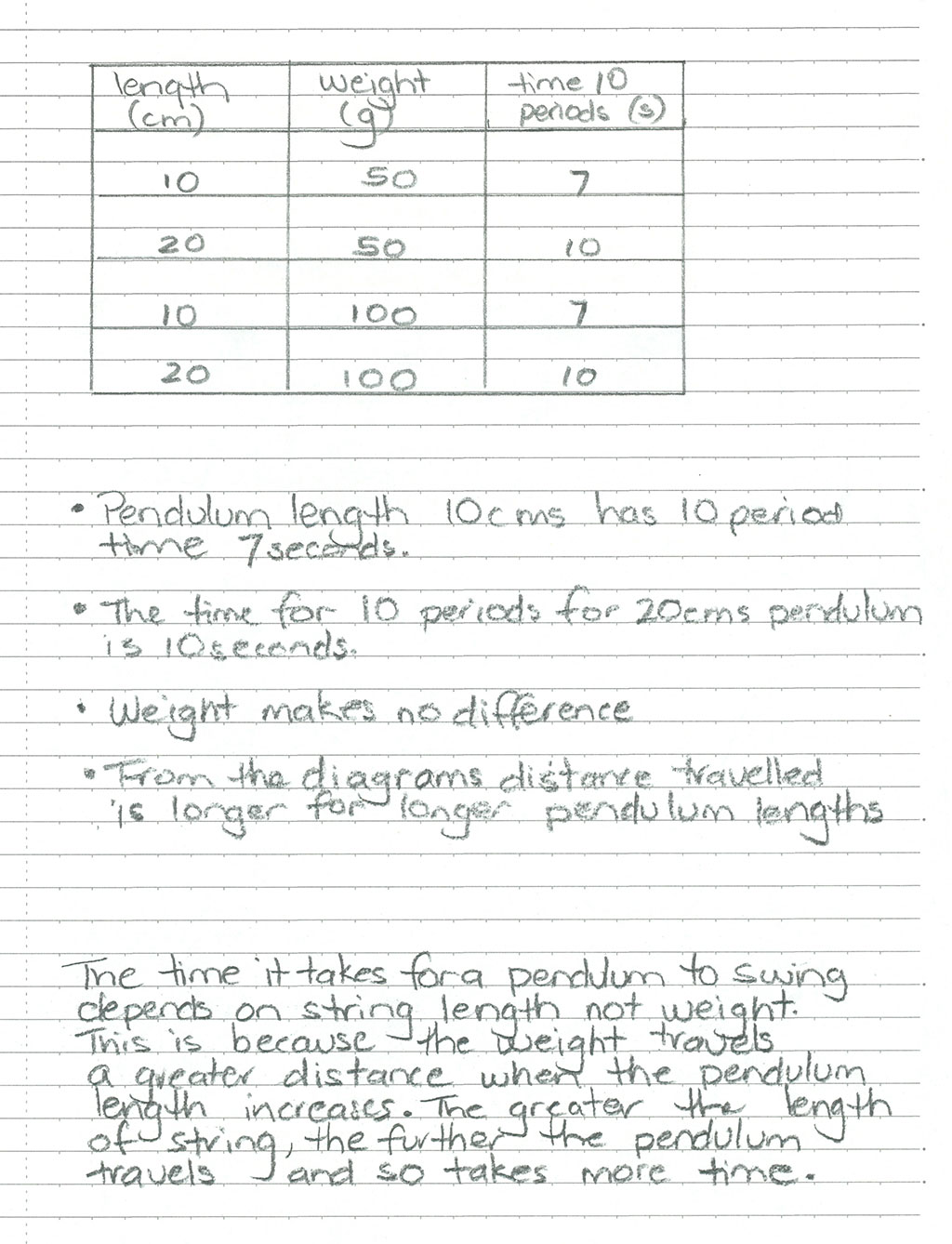

- Students perform an experiment (e.g. measuring flow fourth dimension of a pendulum swing).

- Students draw a diagram to represent their observations (e.g. 2-dimensional diagram of pendulum swing, including pendulum length, weight and measured time).

- Students transform the diagram into a table format (e.chiliad. 3-cavalcade table recording "length", "weight" and "fourth dimension for 10 periods").

- Students analyse their table to write a list of generalisations about their observations.

- Students review their bullet list and rewrite their generalisations in running text form. Make sure students apply connectives and causal links (come across expressing cause and consequence).

View full size image of pupil pendulum caption - jpg 768kb

A note near concept maps

A concept map is a visual representation that shows relationships betwixt and amongst objects, words, or ideas. The use of concept maps is a metacognitive strategy (HITS Strategy nine).

Fisher, Frey and Hattie (2016) propose that the use of concept mapping is well-nigh effective when information technology is used as a tool for students to show their thinking and to organise what they know. In other words, a concept map should non exist considered an end-product; rather, it is an intermediate pace that students can use to consummate another task (Fisher, Frey & Hattie 2016, p. eighty).

Concept maps could take been used to support student thinking in any of the strategies outlined in the other sections. For case, for critiquing and constructing diagrams, students could accept used a concept map to take notes of the various posters they observed. They could then use their concept map to assistance construct their private diagram.

References

Ainsworth, Southward., Prain, V., & Tytler, R. (2011). Drawing to Learn in Science. Science, 333(6046), 1096–1097.

Fisher, D., Frey, North., & Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for literacy, grades Thousand-12: Implementing the practices that work best to accelerate student learning. Corwin Printing.

Jakobson, B., Danielsson, K., Axelsson, Thousand., & Uddling, J. (2018). Measuring time. Multilingual simple school students' meaning-making in physics. In Thou.-Due south. Tang & K. Danielsson (Eds.) Global developments in literacy research for science instruction (pp.167–181). London: Routledge.

Polias, J. (2016). Apprenticing students into science: Doing, talking and writing scientifically. Melbourne: Lexis Education.

Taasoobshirazi, G., & Glynn, S. M. (2009). College students solving chemistry problems: A theoretical model of expertise. Journal of Research in Scientific discipline Teaching: The Official Periodical of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 46(10), 1070-1089.

Tyler, R., Prain, V., & Hubberm P. (2018). Representation structure as a core Scientific discipline disciplinary literacy. In G.-S. Tang & K. Danielsson (Eds.) Global developments in literacy research for science education (pp. 301–317). London: Routledge.

Waldrip, B., Prain, V. & Carolan, J. (2010). Using multi-modal representations to improve learning in junior secondary science. Research in Science Education, 40(1), 65–lxxx.

Source: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/Pages/drawingvisualrepresentations.aspx

Posted by: leehure1986.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Do I Draw A Scientific Model"

Post a Comment